Listening to the audio version of “The Rainy Season”, a novel by one of my favorite authors, James Blaylock, I heard the protagonist mention an old “Daguerreotype print” he found in a trunk and it pulled me up short. I’m guessing he thought, way back in 1999, that it was just another word for “tintype”. It’s not. Even if it were, I don’t think any of these early photographs are referred to commonly as “prints”. “Image”, “plate”, etc., definitely. As a writer, also take care with what process you want to refer to depending on the decade your image is meant to hail from. Photography evolved in leaps and bounds throughout the 19th century, with wildly different chemical processes, base media (like iron or “tin”), and levels of toxicity.

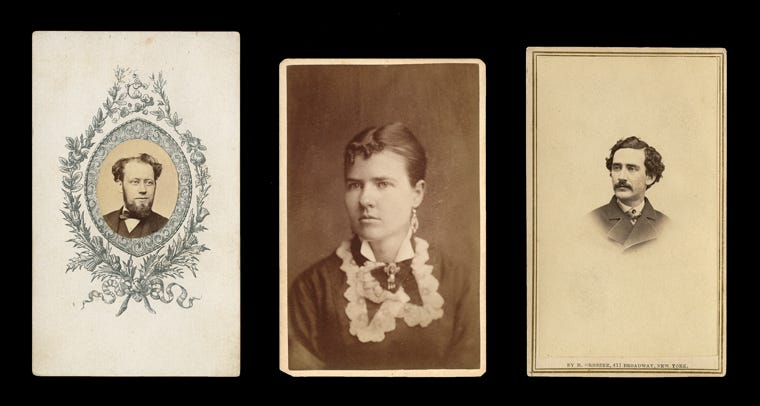

Louis Daguerre announced his process in 1839. In an era when portraiture involved sitting for a painter, the concept of sitting for just a few minutes, at a fraction of the cost, opened up the world of captured likenesses to a much wider segment of society. Still, like the ferrotype (tintype), which hit the ground running a mere decade later, it was a one-off process. There is no negative.

The daguerreotype is a direct-positive process, creating a highly detailed image on a sheet of copper plated with a thin coat of silver without the use of a negative. The process required great care. [Library of Congress, “The Daguerreotype Medium”]

Part of the process involved using vapors from hot mercury to develop the image. Ever heard the term “Mad as a hatter”? Hat makers also used mercury for their process. It’s more than a little toxic and basically eats up your brain. In the 19th century there were no fancy electric fan “hoods” like the ones you find in modern chemistry labs today. Many of these early experimenters died young.

At any rate, when I hear the word “print”, it just makes me think “paper print”. I suppose a carte de visite (or “cabinet card”) is on paper, albeit usually mounted on stiff pasteboard, but those are just “CDVs” to me. Daguerrotypes (“dags”, if you’re an afficionado), ambrotypes (on glass), ferrotypes (Japanned iron plates), and their ilk are all media which usually ended up in cases or frames, with glass to protect the images. Even when varnished (which is the first step in protection for these images), the image is fragile and could be scraped of its base medium.

Anyway, I could drone on for hours about wet-plate photography. If anybody has questions about it, there are many practicing collodion photographers these days, and they’ll be happy to answer questions. Beware of online sources for info. I just ran into an article declaring that average exposure time for a dag was 30 minutes. Maybe for a landscape, but no way is this correct for a portrait. None of them would have been “in focus”, even with the subject glued to the wall. This is like the ‘all teenaged girs had 14” waists’ tightlacing nonsense that gets circulated in historical clothing circles, but I digress. I know a ferrotypist who lives not far from me, Jason Bledsoe (nice article here), and he has plenty of hands-on experience. I’ve assisted him from time to time, and back in the 90s I worked with one of the pioneers of the resurgence of collodion photography, William Dunniway, who was a wealth of knowlege.

Like firearms details (no, revolvers don’t have a safety…except that one weird one), photography is another material culture thing that will draw the nitpickers if you’re not careful. Amongst your beta readers need to be subject matter experts, and it’s easier than ever to find them.